Why your SoA is NOT compliant!

As an auditor, I see the same mistake all the time. Here’s what the standard actually requires.

In my work as an information security auditor, I’ve seen a lot of Statements of Applicability (SoA). And honestly, most of them look the same. It doesn’t matter if it belongs to a multi-billion dollar corporation or a 10-person startup.

What I usually find is a big spreadsheet that includes a a direct copy-paste of ISO 27001’s Annex A, with three extra columns added:

Applicable? (Yes/No)

Implementation Status (Implemented/Not Implemented)

Justification for inclusion/exclusion

But what’s the point of having a SoA?

An ISO 27001 certificate proves that an ISMS was established that meets the requirements of the standard and is capable of achieving the defined information security objectives. Given it’s descriptive nature, being compliant with ISO 27001 doesn’t provide much information about how secure an organisation actually is.

The SoA is supposed to be the key document that gives the certificate context. It’s meant to tell you what’s really going on inside that certified ISMS. It’s the one place that should explain how a company is managing its specific security risks and describe what has actually been done to treat them.

The problem is, most SoAs don’t.

I see this document, which should be the beating heart of the ISMS, treated as a simple administrative hurdle.

This “compliance-first” approach, where you just fill out the Annex A spreadsheet, misses the entire point of the SoA, and it’s probably not compliant with what the standard’s authors intended.

What ISO 27001 Actually Requires

Let’s look at what the standard (in clause 6.1.3) actually requires. It says the organization must:

Determine all controls that are necessary to treat its risks.

Compare those necessary controls with the ones in Annex A to verify that no necessary controls have been omitted.

Produce a Statement of Applicability that contains the necessary controls, the justification for including them, their implementation status, and the justification for excluding any Annex A controls.

The key phrase here is “necessary controls.”

The order here is critical, and it’s the part most people get backward. The standard explicitly asks you to start with your risks and your controls. The comparison to Annex A comes after you’ve done that hard work, not before.

But almost everyone jumps straight to Annex A and works backward, which defeats the entire risk-based purpose of the standard.

Your SoA is supposed to be a list of your necessary controls, not just a report card for Annex A.

Annex A Is Not Your Control Catalog

This is the core misunderstanding. People treat Annex A as a comprehensive control catalog. It isn’t.

What is Annex A? It’s a list of 93 reference controls, organized into four themes. Think of it as a safety net, a final checklist to sanity-check your risk assessment and make sure you didn’t forget an entire category of security.

It is not a detailed “how-to” guide.

Let’s use an example. Look at control A.8.5, “Secure Authentication.” The standard says:

“Secure authentication technologies and procedures shall be implemented based on information access restrictions and the topic-specific policy on access control.”

That’s it. It’s a broad description of a desired state. It doesn’t tell you what technologies to use, how to configure them, or where to apply them. It’s merely a high-level goal.

The standard has to be this way because “secure authentication” means something very different for a global bank than it does for a small internal-only manufacturing tool. The risk is different, so the necessary control will be different.

Annex A is just a prompt. It asks, “Have you thought about authentication?” Your risk assessment must provide the detailed answer. You can’t “implement” A.8.5. You implement actual security controls that help you achieve the goal of A.8.5.

So, What Are “Necessary Controls”?

“Necessary controls” are the specific measures and technologies you decide to implement to treat your risks.

The “necessary” part is the direct output of your risk treatment plan. If your risk assessment says ‘phishing-based account takeover, is unacceptably high,’ your risk treatment plan might be ‘Reduce this risk.’ The how—the specific action you take—that’s your necessary control.

Let’s stick with the authentication example. Your risk assessment identifies that high risk of account compromise. To treat that risk, you determine a “necessary control” is needed.

That control isn’t “A.8.5.” Your necessary control is something specific and actionable, like:

“Implement hardware security keys (YubiKey) for all administrator accounts.”

“Enforce MFA authenticator apps (TOTP) across all cloud services.”

“Implement SAML-based Single Sign-On (SSO) with session timeouts and IP-based restrictions.”

“Use certificate-based authentication for all machine-to-machine access.”

See the difference? These are real, specific, and auditable actions. You can test these. You can verify they are configured correctly. These are your “necessary controls.”

What Your SoA Should Look Like

This changes how your SoA should be structured. The document shouldn’t just list the 93 Annex A controls. It should list your specific controls and map them back to Annex A.

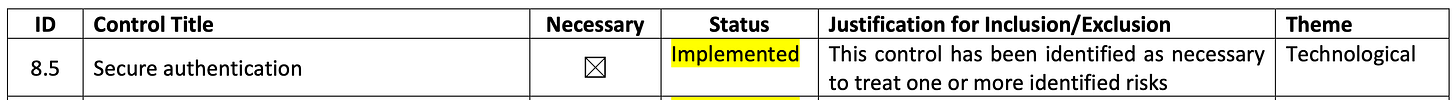

Instead of this common (and less useful) approach:

Your SoA should look more like this, starting with your controls:

Necessary Control ID: e.g. CTR-001

Necessary Control: Access to all critical systems is protected with MFA.

Justification for Inclusion/Exclusion: This control has been identified as necessary to treat one or more identified risks

Status: Implemented

Reference: A.8.5

Where to go from here.

Your SoA is a living document. When it’s built this way, it’s no longer just an audit document. It becomes a central governance tool. It tells an auditor, a customer, or a new CISO exactly what you are doing to manage your risks.

It’s what you use to guide internal audits. It’s what you show new security team members to get them up to speed. It’s a concrete, detailed summary of your security program that you can use to build trust with customers, far more effectively than just showing them the certificate.

While most auditors (including myself) accept SoAs with the Annex A copied, doing what the standard actually has in mind, can greatly benefit your organisation and help build the type of trust you seek to establish.

I think you should consider to upgrade your SoA!

Thank you for the informative blog post. Is there any chance to see a ISO 27001 Lead Auditor course from you in the future? That would be amazing.

Very insightful article. Although seemingly apparent, it is true that most people do not begin with risk. Another confusion I came across is regarding whether one should include clauses too, alongside 93 reference controls, in the SOA for a 2nd line guy, or in an RCM if s/he is an internal auditor performing compliance check. Clause-6 clearly states we should pick and choose from the 93, but this question still pops up from someone or the other. I mean the 93 controls are meant to cover all the clauses right.